Blood and Sand Read online

Page 26

“He fell. No one could have survived that.”

“But—”

Crius gripped her shoulders, forcing her to meet his eyes. “He’s dead. Xanthus is dead.”

Attia pulled away with a wordless cry. The others gave her a wide berth as she staggered past. Then all at once, the world she’d known came crashing down around her. She fell to her knees, dug her fingers into the earth, and wept.

So much had been taken. So many had been lost. And so often, she’d failed the ones she loved. She could all but see their blood on her hands. Maybe Lucius was right. Maybe no amount of penance would ever wipe her clean, and she would carry the memory of her failures to the bitter end. The shame was more profound than any she’d ever known. And she wasn’t sure if it was worth fighting anymore.

With quiet deliberation, tears still streaming down her face, Attia stood and walked to the edge of the cliff. A harsh wind whipped at her hair and tunic, as though it knew the agony that coursed through her.

Lucretia was the only one who moved—the only one who could even begin to understand the urge to stand at the edge and fall. She stood shoulder to shoulder with Attia and whispered, “Come back.”

Why? Attia couldn’t even say the word.

But Lucretia must have heard it in her own way. She reached out and put something hard and cool in Attia’s hand. “Please come back.”

Attia looked down to see the warped remains of her pendant. The iron ring had broken away in jagged intervals, and much of the silver had melted, distorting the edges and giving the once finely carved falcon a hideous tail. Deep black burns scarred the wings so that they looked more like scales, and the waves in its claws looked like deadly blades. Only the stone in its chest remained whole and clear, mocking the emptiness inside of her.

Lucretia left her then, and Attia stared out at the sea, waiting for her thoughts to clear.

“I’m sorry,” Rory whispered behind her.

Attia hadn’t even heard her come close. She turned to look at her.

“I think … I think it was my fault.” Tears tracked down Rory’s face, and her blue eyes were red and swollen.

Attia shook her head. “No,” she said firmly. “None of this was your fault.”

“But you came back for me,” Rory said.

A few feet away, Sabina put her face into her hands and began to sob. Ennius stared at the ground with a glazed look on his face.

“Of course I did.” Attia reached out her arm and Rory hurried into her embrace. “I couldn’t leave you.”

“What happens now?” Rory asked. “Where’s Lucius?”

Attia closed her eyes. How could she tell the child that her family had abandoned her to the fire and smoke? How could she tell her that life would go on, that it would somehow be good again?

How would she ever be able to forget what she’d lost?

“I don’t know,” Attia said. Her voice broke on the last word. It was the only honest thing she could think to say, and yet it was so inadequate. “I don’t know.”

Rory lifted her small face and looked at her. “Don’t worry,” she whispered. “I won’t leave you either.”

* * *

While the others slept—or tried—Attia watched the smoke from Mount Vesuvius unfurl slowly throughout the night. It made her think of the mists that Xanthus said covered his home in Britannia.

He would never again see those rocky hills, just like she would never again see Thrace. But the yearning she’d held on to, the regret and heartsickness, had all transferred onto something else. She’d wanted to go home. She’d wanted to be free. But now she would trade all the minutes left in her life for just one last chance to see Xanthus.

She couldn’t help herself from replaying those final seconds as she watched him fall. But slowly, the better memories came—the first time she saw him truly smile, laughing beside him in the middle of the night, feeling his lips brush against hers and knowing that when she woke up, he would be beside her.

She would never have any of that again. One morning very soon, she would wake up alone. And she feared that more than any weapon she’d ever faced.

So as the long, black night of the Winter Solstice crept on, she kept a new vigil. Not for the gods or her sins or the spirits that waited for her in the underworld. But for Xanthus, for her father, for her people.

For them, she faced the darkness and waited for the dawn.

CHAPTER 26

Albinus woke first. He sat up in the gray light of morning, and his eyes immediately focused on the low-hanging cloud that spread across the horizon. “What is that?” he asked. “Is that smoke?”

“And ash,” Attia said. “Wake the others. It’s time to leave.”

“Have you slept at all?”

“Hurry.”

Sabina and Lucretia stirred a minute later, and Crius barked a threat that Albinus wasn’t to touch him if he wanted to keep his fingers. The others woke to Albinus’s foot in their backsides, and soon they were all mounted and ready to leave.

Attia carefully picked up Rory, who’d fallen asleep in the grass beside her, before handing her to Sabina. The little girl opened her eyes before dropping her head onto Sabina’s shoulder and falling asleep again.

“There’s nowhere for us to go,” Gallus said. His usually smiling face was drawn with grief.

“I can’t even remember what my life was like before this,” Iduma said in a quieter voice than he’d ever used. “I couldn’t get home if I tried.”

“We could keep going north to the mountains,” Ennius suggested. “No one would follow us there in the middle of winter.”

“They wouldn’t follow because they wouldn’t want to freeze along with us,” Crius said. “We should go south to Egypt. The weather will be fair this time of year.”

Albinus shook his head. “Egypt is just another province. We won’t be safe there. The western islands are better. Sicily, perhaps.”

As they argued, Attia tugged on the reins of her horse and turned away.

“And where the hell are you going?” Crius called.

“Rome,” Attia said over her shoulder.

Albinus spurred his horse forward to block her way, forcing her to stop. “I think you may have missed the part where we decided it was in our best interests to avoid the Romans,” he said.

“I am going to Rome,” Attia said again, her voice firm and even. “I am going to find Crassus Flavius, and I am going to kill him and every member of his family.”

The others all stared at her in shock.

“You want to kill the Flavians?” Crius said as he pulled his horse up alongside hers. “Are you mad?”

Ennius frowned. “Attia, I don’t think…”

“You’re a fool if you think you can reach Crassus or that you can assassinate the Princeps of Rome!” Crius shouted.

“It’s suicide, even for you,” Iduma said.

She silenced them all with a look she’d learned from her father. “If the Flavians hadn’t invaded Thrace and Gaul and Britannia, none of us would be here. Our homes would still be standing. Our families would be whole.”

My father and Xanthus would still be alive.

There was fear in Sabina’s warm, weathered face and a wary scowl on Ennius’s dark one. Castor was quiet as ever. The Maedi simply looked at her, all of them warriors she’d known since she was young—gentle Dacian, the twins Rhesus and Teres, sturdy Haemus.

And Jezrael.

She looked at her old friend, her blood-brother, and steeled her voice. “The House of Flavius will fall to my sword. You can either help me or get out of my way.”

Crius sighed heavily. “You are your father’s daughter,” he said with a sad, lopsided smile. “But are you sure you’re ready for this, Attia? Revenge is a dirty business.”

Attia calmly met his gaze. “This isn’t revenge, Crius. This is war.”

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Many of the events and individuals in Blood and Sand are based on true events

, including the eruption of Vesuvius, the destruction of Pompeii, the completion of the Coliseum (also known as the Flavian Amphitheater), and the political undercurrents surrounding the Flavian dynasty. But to say that I took liberties with historical facts here would be like saying that the earth has a slight curve to it. Nearly everything—while rooted in truth—has been altered to fit the narrative, especially when it comes to dates.

It is true that in A.D. 79, Mount Vesuvius erupted over Pompeii, killing thousands and burying the city under layers of volcanic ash and rock nearly ten feet deep. Over the past three centuries, archeological excavations have revealed the surprisingly well-preserved remains of homes, buildings, forums, roads, and even people. Historians have since used the artifacts discovered in Pompeii to provide context for the city’s cultural and architectural facets. According to historical documentation, the eruption lasted approximately six hours, and the few people who escaped the destruction did so by boarding naval ships that had been docked along the coast. The eruption of Vesuvius was so massive that it caused the fall of neighboring cities, including Herculaneum and Oplontis. Wind currents carried surges of heat and ash southward nearly thirty miles to the Gulf of Salerno. It is still considered one of the most devastating natural disasters of the ancient world.

That same year, Titus Flavius became emperor of Rome—not Princeps—succeeding his father, Vespasian. Here, then, is the beginning of the numerous divergences between history and this story. The transition from free Republic to empire is a major plot element in Blood and Sand, but in truth, Rome had already entered its imperial period as early as 27 B.C. Emperor Vespasian—not the fictional Crassus Flavius—was the legatus responsible for invading Britain in A.D. 43. His son Titus earned a reputation during that time as a competent military commander, though he became best known for completing the construction of the famous Coliseum in Rome. He married several times before dying without an heir and was succeeded by his younger brother, Domitian.

The quote at the beginning of Blood and Sand was written by an actual historian who lived in the early Roman Empire, one of many well-regarded men who based their records largely on eyewitness accounts, anecdotal evidence, and word of mouth. Primary documents recording history in ancient times are rather like the culmination of a particularly long game of telephone. That is really how stories were passed along in the ancient world—from person to person, over miles and decades, until they were written down and became canon. And now we come to the crux of this alternative historical fiction: the identity of the rebel slave known as Spartacus. By most accounts, Spartacus lived sometime around 70 B.C., nearly one hundred and forty years before this story takes place. After escaping from slavery with a group of gladiators, Spartacus went on to lead what was called the Third Servile War, in which some seventy thousand freed slaves fought against Roman legions and nearly brought the empire to its knees. Historians agree upon that much, at least. But the details of Spartacus’s identity and early life not only differ but are often wildly contradictory. No one knows who Spartacus was before the war, or if “Spartacus” was a real name or one chosen by the Romans. No one knows where Spartacus was born, what language he spoke, whether he was a soldier or a gladiator, or whether he ever married. And no one can agree on why Spartacus fought the war to begin with, or whether he even survived it.

It may seem odd that a historical figure whose name has inspired songs, films, poems, and novels can be such an enigma. But if there was one major theme that I learned as a history major, it is that history is imperfect because we are imperfect. History is nothing but a collection of stories, colored and twisted and shaped by time and bias and language. It shifts depending upon the lens through which you look at it, and you may find it slowly grow or shrink or change altogether as the years pass and your experiences accumulate. As Napoleon Bonaparte once infamously said, “What is history but a fable agreed upon?” And so my dear, curious, clever reader, I implore you to ask questions and challenge narratives. Facts may be indisputable, but truth is a wily thing. Discover it for yourself, and maybe somewhere along the line, you’ll see the world—and its possibilities—in an entirely new light.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Telling a story and sharing a story are two very different things. The first can be a solitary, often isolating experience, whether by necessity or circumstance. But the second—well, that’s a horse of a different color. Sharing a story with the world, giving it a name and a cover, finding it a home on shelves and in hands takes the passion, faith, and dedication of every person who comes in contact with it. Those people deserve to be named and thanked, as well as I can. So here they are, the glorious folks who’ve stuck around, supported me and this story, told me when I was royally screwing things up and then giggled with sheer joy when I finally got something right. Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you.

To my parents, for their constant love and willingness to buy me all the books I asked for, even when those books started to take up more space in my room than clothing or furniture.

My teachers and mentors from middle school to college, especially Mrs. Tisdale, Deborah Hoffman, Francille Bergquist, Helmut Smith, Vereen Bell, and Katherine Crawford.

The people who cheered for this book before even reading it and kept me going with virtual cookies and very real words of love: Tiffany Flecha, Kelsey Tricoli, Katilyn Walker, Jessica Scales, and Anna Priemaza.

One of my oldest friends, Ben Quigley, who’s been willing to read my words—the good, the bad, and the oh so damn ugly—since we were eighteen.

My lovely, bright-eyed agent, Sandy Lu of L. Perkins Agency, who has advocated and fought for me, and who may or may not have missed a subway stop or two while working on this book.

My editor, the tireless Susan Chang, who devoted tears and sweat and probably years off her lifespan to this story, as well as the entire team at Tor, from artists to copy editors, who have helped me make this debut as good as it could possibly be.

To my literary sister, Dot Hutchison, who wove her own stories with equal parts magic and possibility, who shared her knowledge and passion for fiction, and who ultimately made me believe that I could write this book at all. It exists because of you.

To my adopted sister, Katrina Cuddy, who found me when I was lost, who is bound to me by love rather than blood, and whose unwavering loyalty has given me more strength than any creed I have ever known. I’ve survived because of you.

And to Karl, who has made me the kind of vows you make in the soul. Who knows me down to my bones and loves me anyway. Who has kept so very many vigils with me in the dark, and who has helped me turn to face the light. I am because of you.

Read on Page for a preview of

FIRE AND ASH,

coming soon from Tor Teen.

CHAPTER 1

They called for her in the darkness. In the quiet. The voices of the dead reached through the ether with words like blades. A cacophony of whispers and cries and furious epithets.

Disgrace. Coward. False queen.

And when Attia closed her eyes, she saw them: the faces of all the ones she couldn’t save.

It had been three days.

Pompeii was gone, buried under a mountain of fire and ash. A strong western wind blew in from the Tyrrhenian sending slate-gray smoke billowing out for miles in a suffocating fog, its edges sharp with the screams of the dying.

Attia and her people could barely outrun it. Their horses began to stumble with the burden of their retreat. They didn’t have the luxury of stealth. Crius and the other Maedi knew a dozen different routes between Pompeii and Rome. But the paved main road was the most direct, and as the third day passed into the fourth, whatever apprehension they had about being caught by the auxilia or vigiles was burned away by the relentless flames spreading inland.

Herculaneum fell. Then Oplontis. And suddenly, they weren’t the only ones running.

The other cities must have had some warning because there were survivors—thousands of them.

An exodus of displaced Romans venturing north and east, fleeing the wrath of the gods. The flood of bodies—plebeian and patrician, slave and free—swept over the countryside like a wave.

Among them, Attia and her people could be anyone and no one. Still, they kept to themselves, forcing their tired limbs to move until the sun set on the fifth day and they could finally stop. It was the first time they’d been able to rest since the sky started burning.

Attia’s eyes were red and heavy with exhaustion. She collapsed onto the grass with the others, and her lids began to fall shut. But all at once, the faces and the voices rushed in, crowding out every other thought in her head. She jerked awake, gasping for breath. There would be no sleep for her. The souls of the departed haunted her, and she found she could not face them.

She’d once thought it was Xanthus’s curse to remember and hers to forget. But as she sat there with her demons and her ghosts, she wished for oblivion. She wanted to forget the faces and the voices. She wanted the void. She wanted the darkness.

But not death. Not yet.

Attia glanced over her shoulder at the others. Sabina and Lucretia sat curled together around Rory and the little boy, Balius. The gladiators and the Maedi had formed a loose circle around them, some resting, others keeping watch. In a shallow valley just to the north, Linus slept with the horses.

What a strange, broken family they made. Attia wondered again why they’d chosen to follow her. They were no longer slaves. They’d survived, and they were free. And Attia was no general. Certainly not a queen. Was she even a Thracian anymore? She didn’t know. She didn’t know anything, except that Rome would burn—and that she would be the one to light the flame.

She looked up at the smoke-dimmed stars overhead. Five days. It had been five days, and she could still hear his voice. Xanthus. He’d come back for her. He’d kept his promise, and died. For her.

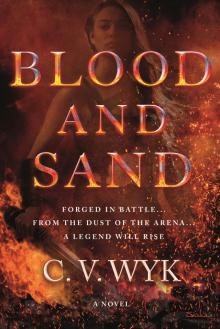

Blood and Sand

Blood and Sand