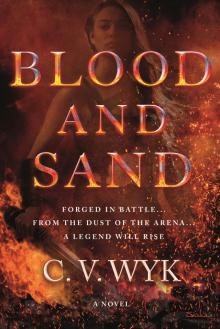

Blood and Sand Read online

Page 9

“You don’t have wrinkles, Domina,” Lucretia said.

Valeria scoffed, but a pleased smile crossed her lips. “I don’t look my age, do I? Not even two children could rob me of my figure. Let Flavius choke on that.”

The name made Attia stiffen with interest. She dipped her fingers into the cream again and mindlessly added another layer to Valeria’s face, her attention focused on the woman’s continued chattering.

“Titus could barely hold that wife of his for a year. What does he know about women? His cousin Tycho is a toad, and if Crassus weren’t a father, I’d wonder if he’d ever bedded a woman at all.”

Lucretia muttered in agreement, though Attia wasn’t sure if she was even listening.

“Married three times and only one son. What does that tell you?” Valeria said with a smirk. The expression quickly turned bitter. “And if he sired any daughters, well, I wouldn’t be surprised if those girls were plucked from their mothers’ breasts and thrown into the Tyrrhenian. We all know how Flavians treat their women.” Her mouth curved in a grimace.

Attia wore a ferocious frown as she listened to Valeria. Was all that true or was Valeria simply repeating some cruel rumor? But Attia thought of the complete lack of women on the Flavian family tree in Timeus’s study, and chills blossomed across her back.

“Of course, my brother hopes the Princeps will be at the next match,” Valeria was saying. “As long as Crassus and the Toad stay at Palatine Hill, I’ll be fine.”

So that’s where Crassus was staying. It made sense. Where did a soldier go when he returned from war or a massacre? Home, of course.

The irony of the situation wasn’t lost on Attia. She’d wanted to go to Timeus’s study to look for information on Crassus. Who knew that she could simply have visited Timeus’s sister and listened to the latest gossip?

The corner of Attia’s mouth lifted in a muted smile, and she focused her gaze on Valeria’s face. The woman’s already pale skin was practically white now—thickly layered with the special lavender cream from Naples. Attia quickly put the bowl down and searched for another color to put some life back into the older woman’s skin. She found a jar of something red, and when she removed the cork lid, the scent of wax wafted out.

The stuff inside was stiffer than the cream, more solid. Attia vigorously rubbed the surface with the pad of her finger to pick up the color, and then tried to apply it to Valeria’s cheeks. But the pigment was just as unyielding on skin as it was in the jar. Two bright red spots stood out on Valeria’s high cheekbones, and no matter how Attia rubbed at them, the color refused to fade or blend away.

Attia quickly grabbed a shallow plate of bronze powder from the vanity. With a piece of linen, she spread the powder all over Valeria’s face, focusing mostly on the red spots. She stood back to consider her handiwork.

Well, the red spots had diminished, and Valeria no longer looked pale. No, now she just looked as though she’d been burnt too strongly by the sun. Or acquired some foul infection in Naples.

Attia glanced over her shoulder at Lucretia, who was still busying herself with Valeria’s gowns. There’d be no help from her, apparently. Attia scowled with irritation and snatched the jar of black paste from the vanity. It wasn’t as thick as the red stuff, nor as soft as the cream, but it stuck to her finger like tar. Not wanting to get the black paste all over her hands, she selected a thin brush and swirled its stiff bristles around in the pot. She bit her lip in concentration as she slowly drew thick lines along Valeria’s blonde lashes—a look that Timeus’s concubine seemed to favor. Attia allowed herself a satisfied smile before drawing matching strokes along Valeria’s bottom lashes.

Only when Valeria opened her eyes again did Attia get a good look at the horror she’d wrought.

Oh. Gods.

“Don’t forget the lips, girl,” Valeria said—oblivious—and closed her eyes again.

Lucretia chose that moment to approach. She took one look at Valeria, and her blank expression changed to one of shock. Her jaw dropped, her eyes widened, and she clapped her hands to her mouth in an obvious effort to keep from laughing.

Attia aimed a furious scowl at her as she reached once more for the bowl of red goo. That seemed to knock Lucretia back to reality, because the neutral mask fell into place again, and she took the bowl from Attia’s hand.

“I’ll finish this up for you, Domina,” she said, lightly pushing Attia aside. She didn’t meet Attia’s eyes, only nudged her head toward the door.

Attia didn’t need to be told twice. She hurried out the door, fighting the urge to run and stifling her own laughter as she went.

CHAPTER 9

It was all Valeria’s idea.

As Attia returned to the villa from Xanthus’s room the next morning, Valeria called to her from the eastern sunroom where she, Lucius, and Timeus were breaking their fast.

“I want to bring her with us, Josias. Rory likes her so much already, and you know, she and Lucretia helped pick my outfit just the other day. Let me bring her,” Valeria said in a cloying voice. “She can stay up on the veranda with us. I’m sure she won’t bother anyone.”

Timeus said nothing at first, though the line of his mouth tightened as his sister chattered on. But after a few minutes, a thought seemed to occur to him and he frowned. “She could watch,” he said quietly, almost to himself.

“Yes! Yes, exactly!” Valeria said in her animated voice. “She can attend to me and watch. Wouldn’t that be wonderful?”

“And he’ll know,” Timeus murmured. “He’ll know she’s there.”

“Yes, of course!” Valeria laughed, though she clearly didn’t know what Timeus was talking about. “So we’ll bring her?”

Timeus turned to glare at Attia. “Yes,” he said. “We’ll bring her.”

The look on his face sent chills racing along Attia’s skin.

That afternoon, Attia again found herself being led through the streets of Rome. A slender bronze chain wrapped around her waist and tied her to Valeria’s litter as befitting the domina’s handmaiden. The chain was more for decoration than anything else—proof to anyone looking that she was property. Four strong slaves carried the litter down the street.

Up ahead, Timeus and Lucius rode in a large draped lectica, a more opulent version of Valeria’s stupid basket, with tall gold posts and the backs of over a dozen slaves to carry it. The gladiators followed in the rear, with Xanthus at the front of the group. Attia tried to catch a glimpse of him, but her line of sight was obscured by the other slaves and the crowd.

Turning her face up to the light, Attia tried—for a moment—to forget where she was. But even without looking, she could count the footsteps of Timeus’s private guard and distinguish the vigiles from ordinary citizens. She could smell the odor of crowded bodies. She could sense the nearly empty space in the plaza just to the west.

Attia scrutinized the façades of the buildings and measured the distance between the main road and the tiny alleys that branched off in every direction. She could run there, then there. She could use that window and that ledge. That fat vigil wouldn’t be much bother, though the young one next to him was fit and athletic.

But this time, the impulse to escape was tamped down by another darker urge. Timeus had to die. She trained her eyes on the back of the old man’s head and let her hand brush against the fold in her tunic where she’d hidden the little knife. She knew she couldn’t—wouldn’t—run while Timeus still drew breath. Besides, if she tried to escape now, it would be like the day of the auction all over again—she’d be hunted through the streets by every vigil in the vicinity, witnessed by hundreds. The only way she could safely run from Timeus’s household was if she killed the man first. With no one to chase after her, she could then focus her rage on Crassus.

Consoled by her plans, Attia forced her thoughts back to the present, looked up, and got her first clear look at their destination.

The Coliseum was a massive circular structure, freestanding and made of

a neutral-colored stone. The top of it pushed at the clouds, and flocks of birds dipped and dove around its edges. Hundreds, thousands of miniature arches marked the face of it like so many eyes, and a muted roar echoed from its center.

“Gods,” Attia whispered.

Valeria sat up in her litter and drew her veil aside. “Construction was completed just last summer. It is a true wonder.”

Attia couldn’t disagree. Before she came to Rome, she never would have believed that men could build something like this. What a shame that such a magnificent achievement was done for such a bloody purpose.

The caravan reached a high archway at the base of the Coliseum, where a round man greeted Timeus with open arms. He wobbled as he walked and looked like he hadn’t been sober in years.

“Timeus, Lucius! And lovely Valeria,” he said in what he probably thought was a deep voice but only reminded Attia of a cow passing gas. He took Valeria’s hand to kiss it.

“Sisera Trevana, a pleasure,” Valeria said, smiling graciously even as she pulled her hand away and wiped it subtly on Attia’s sleeve.

They passed through a short tunnel before the group began to split off. A few guards and house slaves accompanied Timeus, Lucius, Valeria, and Sisera to a set of stairs. The rest of the guards, the gladiators, and the slaves who carried the litters turned toward a descending ramp that seemed to lead deep into the bowels of the Coliseum.

Attia turned to Xanthus, hesitant and awkward. Sunlight reflected off a pendant that hung on a leather cord around his neck—a silver crescent moon—and Attia stared at it, not quite willing to meet Xanthus’s eyes. She had no idea what to say to him. And she certainly didn’t know what to do when Xanthus leaned toward her and kissed her temple. The light caress was so tender and so wildly unexpected that Attia felt a fluttering sensation deep in her belly. Then he turned away and followed the other gladiators down the ramp.

Attia stared at his retreating back until Ennius called her name. Together, they slowly climbed up several flights of shallow stairs to the shaded upper level of the arena.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve had to climb up to some veranda or balcony to watch my boys fight,” Ennius said.

“Too many?” Attia suggested.

Ennius smiled bitterly. “Yes. Too many.”

A dozen armed guards lined the last few steps, and even more arranged themselves in strategic spots around the veranda. Timeus, Lucius, and Sisera reclined in gilded seats behind a man whose face Attia couldn’t see. Valeria and a few women sat behind the men, and Lucretia stood just a few feet away, still as a statue. The rest of the slaves lined the back wall. Attia positioned herself near the edge of the balcony and looked down into the heart of the Coliseum.

It was magnificent. Three stone levels rose up around the arena with smaller rows of seats that doubled as steps. The veranda occupied prime position at one end, not too high nor too low, with heavy awnings to shield its occupants from the sun. The marble railings were ornately carved, and the whole space smelled of incense, probably to mask the copper tang of blood.

The sections closest to the veranda were populated by men in immaculate white robes. Attia guessed they were members of the Senate. Another section was filled with patricians in brightly colored clothing and sparkling jewels. The largest section—the rows farthest from the arena floor—jostled with dirty, hungry people who reached over their neighbors to catch the bread being thrown upward by a row of armed guards.

Panem et circenses, as the Roman poet said. Bread and circuses. Attia had never realized how literal the phrase was.

A short blond-haired woman nudged Attia’s arm. “Don’t fall over,” she said. “I almost fainted the first time my dominus brought me up here to the primum. But perhaps you are made of sterner stuff.”

“Your dominus?”

“I belong to Sisera,” the woman said. “And I’m guessing you belong to Timeus.”

Attia wanted to hit something. “I don’t belong to anyone.” She felt like she’d said the words a hundred times since she arrived in Rome.

The woman gave her a sad smile. “But you do.”

Attia turned her face away.

“They call me Aggie,” the woman said. “What do they call you?”

Her choice of phrase struck Attia, who tried to remember where she’d heard it before. “What do you mean by that?” she asked.

“Well, I wasn’t born with that name,” Aggie said. “I come from Gaul.”

And then Attia remembered. Xanthus had said something like that to her. They call me Xanthus. It had sounded odd at the time, but Attia hadn’t thought of it again. Not until now.

Attia looked back at Aggie. “Then what was your name before?”

“It was Galena. I’ve always liked it for all that my mother wasn’t particularly original. You?”

“I am Attia.” But she frowned as she said it. Had Sabina been renamed? What about the other slaves in the household? Her eyes drifted to Timeus’s concubine. Had she been given a new name as well?

The man sitting in the first row of the veranda threw something over the rail—a piece of fabric—and motioned to Timeus.

“Start it already,” he said. “I’m getting bored.”

Attia still couldn’t see his face, but she saw the gold circlet nestled in his auburn hair and the massive ruby ring on the smallest finger of his left hand.

“Who is who?” the man asked.

Timeus looked at Sisera. “We hadn’t decided that yet.” He produced a gold coin from a pocket in his robes and looked at Sisera. “You choose.”

“Heads,” Sisera said.

Timeus flipped the coin into the air, caught it, and slapped it onto the back of his hand. “Tails,” he said. “Better luck next time, Sisera. Your men can play the Trojans.”

Sisera groaned. “Every damn time,” he muttered. He stood and introduced his gladiators as six men rode into the arena. They carried lances at their sides and wore plumed helmets on their heads. One gladiator, who was apparently playing Hector of Troy, wore a bright blue sash across his chest. Sisera seemed to go on for a long time, nearly shouting about the honor of the Trojans, their skills in battle. When he finally finished, he collapsed into his chair, mopping his brow with a piece of linen.

“Finally,” Timeus muttered. He turned to Lucius. “How about it, boy? You’ll have to do it someday.”

Lucius shook his head. “You are much better at it, Uncle.”

“You can’t say no forever,” Timeus replied, but he got to his feet all the same, walked to the edge of the veranda, and raised his hands for silence. “Romans,” he began, and although he didn’t shout as Sisera had, his voice carried across the entire arena. “The great poet Homer once told us of the epic battle between the Greeks and the Trojans…”

Attia’s focus shifted as Timeus went on. Her father had told her about the Trojan War, how a spoiled prince and an arrogant king battled over a woman so beautiful that her face launched a thousand ships. Attia remembered laughing at that.

“How can a face do that? You need two dozen strong men, at least, if it’s a long ship,” she’d said.

Sparro hadn’t so much as smiled at her naïveté. “I don’t mean it literally, Attia. Helen was famous for her beauty, and her husband Menelaus was angry to lose her. But she was not really the reason for the war. She was an excuse.”

“But you said that the king and the prince fought over her.”

“Yes, but…” Sparro had put his hands together and tapped his long fingers against his chin. “Agamemnon—the brother of Menelaus—used his brother’s anger as an excuse to attack Troy. It was a very wealthy city.”

“So … they fought for gold?”

“And power, yes.”

Attia shook her head. “That makes even less sense than fighting for love.”

At that, her father did laugh, but she hardly minded. She was only a child, after all.

Timeus’s version of events was markedly different. He sp

oke not of love or even ambition, but of ruthlessness and cunning, of strategy and superiority. And then when he introduced his gladiators, he called them something else—neither Greeks nor Trojans. He called them Myrmidons.

Attia sighed with recognition, finally seeing his game. If the gladiators were Myrmidons, then Xanthus could only be Achilles, and even the illiterate of Rome knew that Achilles slew Hector. Timeus obviously believed his gladiators’ victory was inevitable. If it had been any other men down in the arena, Attia would have paid the boatman herself to see them all on a one-way trip to the underworld. But Xanthus was down there, or soon would be, and she found herself hoping that Timeus’s confidence was warranted.

The old man raised his hands again. His next words were spoken in such a distinct cadence that Attia thought he’d probably spoken them hundreds of times before. “Our champion needs no introduction. Call his name! Release his fury!”

And instead of calling for Achilles, the entire Coliseum shook with the force of another name. “Xanthus! Xanthus! XANTHUS!”

A loud creaking echoed from somewhere far below as the gate to the hypogeum opened. The crowd became nearly hysterical with excitement when they saw Xanthus walk out onto the sand.

Even from a distance, he looked intimidating—all muscle and bone and pure, deadly force. His black armor wasn’t armor at all, but a leather breastplate and greaves that were meant to show off his body rather than actually protect him. He had no shield, only two straight swords strapped to his back. He didn’t even have a helmet, and the tips of his dark hair seemed to turn gold in the sun.

The five other gladiators who fought with him were also dressed in black, but they carried round shields, and their armor covered everything but their arms and knees. They raised their swords to Xanthus as if he were truly Achilles—he their commander and they his loyal soldiers.

At the very center of the arena, Xanthus turned to look up at the veranda. With a single fluid motion, he unsheathed his swords and struck them together over his head with enough force to send sparks flaring along the bright metal.

Blood and Sand

Blood and Sand